Share

Britain is falling behind Russia in the undersea domain, leaving vital data cables and energy infrastructure exposed to disruption and sabotage, MPs have been warned.

In a one-off evidence session, the House of Commons Defence Committee heard that Russia is already using submarines and deep-sea platforms as part of a sustained campaign of hybrid warfare, targeting critical infrastructure below the threshold of armed conflict.

Witnesses said the oceans remain effectively opaque, making it extremely difficult to detect hostile submarines once they enter the North Atlantic. Submarines, they stressed, remain the only military capability that can pose a persistent, unseen threat, with no equivalent alternative.

Professor Peter Roberts told MPs that while Britain is distant from the land fighting in eastern Europe, the picture is very different beneath the sea.

“Yeah, absolutely,” he said, when asked whether the UK is effectively on the front line underwater. “The UK hosts 119 data cables, around $17 trillion worth of trade [a day] passes through UK data cables. It’s the gateway to Europe, it’s the gateway to the Mediterranean, and in data cable terms it’s the gateway for Europe into the United States.”

He added that Britain’s exposure goes far beyond communications.

“The energy pipelines are enormous connectors through the UK. So the UK is on the front line,” Roberts said. “And more than that, President Putin has expressed, both in his doctrine and in his speeches, his desire to strike at the UK directly.”

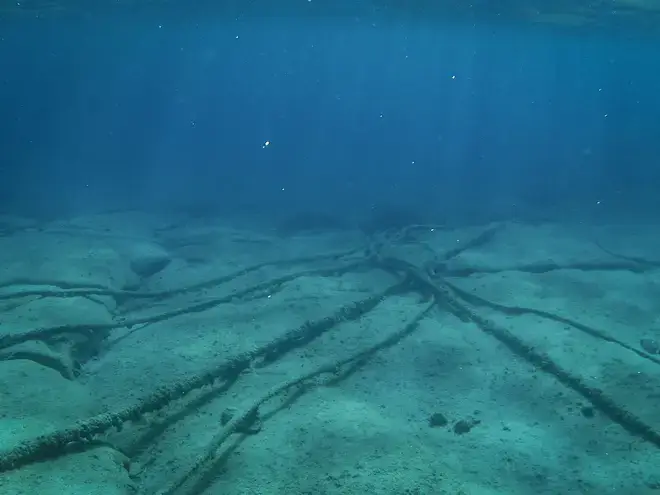

“For the UK, there are around 119 data cables, and while they are armoured as they approach the shore, for most of their length across the seabed they have no protection at all,” said Prof Roberts. “They can break simply because a water current pushes them against a rock.

The expert warned there were hundreds of breaks to undersea cables every year.

“On average there are about 190 cable breaks every year around the UK, and most are fixed. When the Shetland Islands were cut off in 2020 after fishing vessels damaged the cables, the connection was restored within a week. Internet service providers will tell you there is sufficient redundancy in the system, and that is why they say they are not worried.

“But the reality is they do not know what is happening around those cables on the seabed. In UK waters alone there are around 42,000 kilometres of undersea cables, and monitoring that environment is extraordinarily difficult.”

Witnesses warned that Russia is using submarines and deep-sea platforms as part of a wider campaign of hybrid warfare, targeting infrastructure in ways that are difficult to detect, attribute, or deter. Submarines were described as uniquely dangerous because they can operate unseen across vast areas of ocean, posing a persistent threat to cables, pipelines, and offshore assets.

“The seabed is becoming a battlefield in a way we haven’t seen before,” said John Aitken, a former Royal Navy commodore. “It is an extremely difficult environment to operate in, even at relatively shallow depths. Something as basic as the weather can determine whether systems can be deployed or supported, particularly in the North Sea and the North Atlantic, which are hostile environments for much of the year."

The committee heard that once a hostile submarine is operating freely in the North Atlantic, tracking it becomes extremely difficult, limiting the UK’s ability to respond. While the Royal Navy operates world-class submarines and sonar systems, experts said Britain lacks the scale and resilience needed to maintain constant undersea awareness.

Autonomous underwater vehicles were described as valuable supplements, extending surveillance and reducing risk, but not replacements for crewed submarines. Fundamental limits around power, communications, and reliability mean autonomous systems cannot yet provide comprehensive protection.

MPs were also warned that the legal framework governing undersea conflict has failed to keep pace with the threat, with much of international law still rooted in nineteenth-century agreements.